The Feasibility of Providing Periodic Health Assessments to All Primary Reservists

Executive Summary

For the last quarter of a century Reservists have participated in expeditionary operations in the Balkans, the Middle East and Africa, and humanitarian crises such as in Haiti and the Philippines, largely as augmentees to the Regular Force. Although it is almost impossible to predict the future needs of the Armed Forces, contemporary global conflicts indicate that Reservists will continue to be integrated into future expeditionary missions.

Also, Reserve Forces are increasingly tasked during domestic operations such as providing security at international events and responding to natural disasters. Reservists are ideal for missions within Canada as they are located in communities throughout the country. The Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) depend on their Reserve elements for arctic and coastal defence.

Notwithstanding the increased requirement to employ Reservists on expeditionary and domestic operations, it is imperative to ensure that Reserve Force members are fit to conduct regular training and exercises, which is at times challenging and strenuous. Universality of Service mandates that all Primary Reservists must be free of medical conditions that would limit their ability to be employed and deployed. Further still, commanding officers are responsible for the health and wellbeing of Reservists under their charge, and must attest yearly that their personnel are medically fit.

There is a divergence between the administrative need to have a medically fit Primary Reserve, and the requirement to adhere to medical regulation. The Queen’s Regulations and Orders Chapter 34-Medical Services, which was last updated in 1985, stipulates that Reserve Force personnel are only authorized to receive a periodic health assessment (PHA) if the requirement is directly attributable to the performance of a specific military duty. In its current iteration, Chapter 34 of the Queen’s Regulations and Orders is vague in almost all areas of Reserve personnel’s entitlement to medical services and this ambiguity leads to different interpretations and applications and a considerable amount of healthcare providers’ time is devoted to determining entitlements.

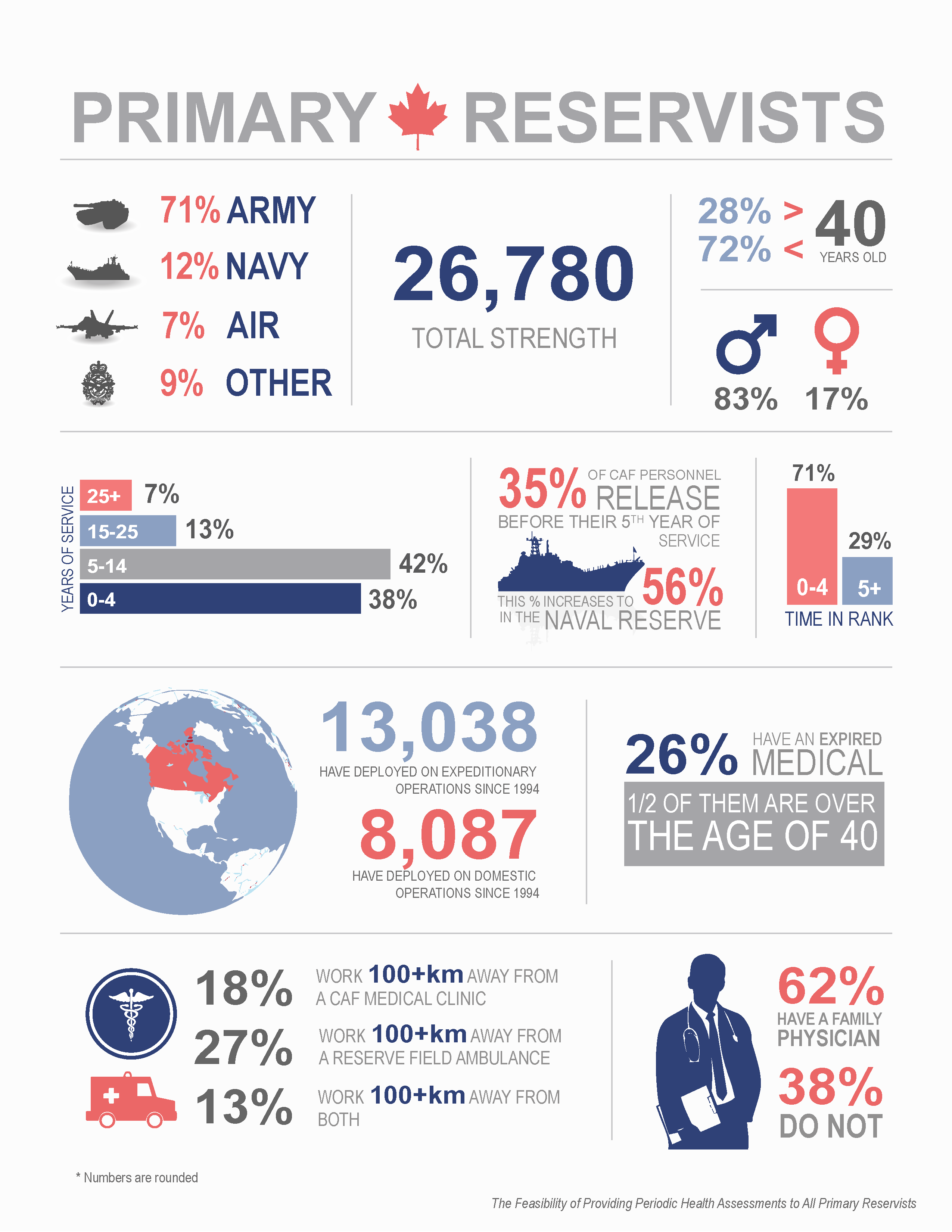

The Total Strength of the Primary Reserves is 26,777, 28% of which are over the age of 40. 26% of Primary Reservists do not have a current medical on file. Although Reservists generally receive health care services from the province in which they reside, 38% of those polled do not have a family physician.

The purpose of this study was to examine and report on the feasibility of providing PHAs to members of the Primary Reserve at the same standard of periodicity as the Regular Force. It is projected that between 4,881 and 6,106 medical assessments would be conducted in a given year in order for Primary Reservists on Class “A” service to be provided with PHAs at the same standard as the Regular Force.

There are over thirty CAF health services centres (clinics and detachments) located throughout Canada. Several CAF health services centres have identified possible resource constraints should they be required to take on the additional periodic health assessments and the Chief Military Personnel’s business plan for 2015-2016 noted that sustainment of the current level of health care will result in increasing funding pressures.

Providing PHAs to all Primary Reservists could be feasible if other courses of action are considered. Preliminary research conducted as part of this study examined potential options and the Canadian Health Services Group has also reviewed other ways to provide Primary Reservists with assessments of medical fitness separate from this study.

The Canadian Forces Health Services Group will further investigate all courses of action in greater detail to determine the valuation of each of the options, including full costings, and will prepare a follow-up report on its findings.

Section I - Introduction

TheCanadian Forces Health Services Group administers Canada’s 14th healthcare system and is mandated to deliver health programs and services to the CAF. It manages an occupational medicine component, which includes continuous medical screening of personnel such as upon enrolment and release, prior to and following deployment and when promoted or moving to an isolated post. PHAs are also provided at regular, defined intervals thus certifying a member is medically fit to be employed and deployed.

The CAF is comprised of two components: Regular Force members, who are contracted on full-time continuous service and who are compelled to work and deploy at Her Majesty’s behest; and Reserve Force personnel, who are employed mostly part-time and who may choose to sign up for tasks and missions, if their service is required.

Regulations, orders and directives clearly stipulate that Regular Force personnel receive their health care from the CAF. Entitlements for Reservists are less discernable and more incongruous. For example, regulation states that Reservists on part-time service are authorized to receive health care only if the requirement is attributable to service, yet a member must have a valid assessment of fitness in order to be employed. In terms of periodic health assessments, some argue that Reservists are not entitled as per regulation, and others contend that Reserve Force personnel’s fitness to serve must be regularly attested and therefore they require the medical screening.

Whereas the Reserve Force was once maintained as a strategic asset it has become more operationally engaged in the last couple of decades. Notwithstanding the increased requirement to employ Reservists on expeditionary and domestic operations, it is imperative to ensure that Reserve Force members are fit to conduct regular training and exercises, which is at times challenging and strenuous. Reservists could be performing less physically demanding tasks such as sitting at a school or office desk all week, and then on the weekend participate in a military exercise where they are expected to carry a pack on their back and march several kilometres on two hours’ sleep, or fire weaponry on a range or operate heavy machinery and drive vehicles with passengers.

As commanders are responsible for their subordinates’ health and wellbeing, those who lead Reservists require assurance that their people meet the standards for employment and deployment and are physically able to effectively participate in tasks and training. CAF medical personnel understand the need and want to provide the service, but they are hindered by out-dated policy, confusing interim guidance and a lack of resources. All the while, politicians, watchdogs and advocacy groups are concerned with Reservists’ equitable entitlement to health services provided by the military.

Study Background

The Office of the Ombudsman for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces (DND/CF Ombudsman) has raised concerns about the lack of consistency in the provision of PHAs to Regular and Reserve Force members. In the 2008 report Reserved Care: An Investigation into the Treatment of Injured Reservists and its 2012 follow-up, the Ombudsman recommended that PHA standards be applied equally to Regular and Primary Reserve Force personnel. Although the Department of National Defence and the Candian Armed Forces (DND/CAF) aims to provide PHAs to all Primary Reservists, the scope of the resource requirements (money, time and personnel) remains unclear.

Since 2010 the Canadian Forces Health Services Group has performed two proof of concept trials by providing PHAs to Reservists at pilot sites, but does not have the capacity to conduct a comprehensive study to determine the global investment required. Recognizing this limitation, the DND/CF Ombudsman offered to partner with Canadian Forces Health Services Group to conduct the PHA study, which began on September 2nd 2014.

Aim

The purpose of this study was to examine and report on the feasibility of providing PHAs to members of the Primary Reserve at the same standard of periodicity as the Regular Force.

Objectives

There were three objectives in undertaking this study:

- Conduct a detailed review of the Primary Reserve cohort. This activity involved determining the unit of each member and mapping them against where CAF medical resources exist. Also, demographic data was assessed to determine trends that may impact the resources required to provide PHAs to Reservists.

- Review the medical capabilities available within the CAF, as well as examining other potential resources such as other federal governmental organizations that conduct occupational health assessments and civilian family physicians.

- Tabulate resource requirements such as personnel, materiel and financial costs associated with the delivery of PHAs to all Reservists.

Research conducted on other potential options and on resource requirements in providing PHAs to Reservists requires further review by the Canadian Forces Health Services Group to determine the valuation of each of the options, including full costings, and will be included in a follow-up report.

Scope

The Reserve Force is comprised of the Primary Reserve, the Supplementary Reserve, the Cadet Organizations Administration and Training Service, and the Canadian Rangers. Members of the Primary Reserve regularly train and may be employed on operations and taskings. Primary Reservists are the focus of this report. Any reference to “Reservist” or “Reserve Force” in this report should be construed as a member of the Primary Reserve.

Methodology

The methodology is detailed in Annex A.

Section II - Context

Today’s Reserve Force

Up until the mid-twentieth century, the Reserves were retained primarily as a strategic defence asset that could be activated en masse for a large-scale conflict, such as the First and Second World Wars, or even to prepare against a more ethereal threat like the Cold War. As noted by Richard Weitz, author of The Reserve Policies of Nations: A Comparative Analysis, the major benefit in maintaining a Reserve component was that it provided flexibility at a reduced cost, as Reservists were kept at a lower level of readiness.[i]

Total Force is a theory first introduced in the United States after the Vietnam War. In simple terms, Total Force is the integration of both military components (Regular and Reserve), with the two maintained, equipped and trained at comparative levels. Canada adopted the concept in the late 1980s.[ii] However, it is important to note that the notion of Total Force has never been formally recognized in any statute or Treasury Board guidelines.[iii]

Although the Reserve Force has evolved from a fighting force in waiting to an integral component of the Total Force, the DND/CAF is lacking a clear statement on the role of the modern Reserve Force, as noted by the Chief Force Development in its 2011 report on the Primary Reserve Employment Capacity Study.[iv] The Vice Chief of the Defence Staff launched the study in October 2010 with the primary deliverable to determine the baseline for full-time employment of Reservists. The final report also recommended a vision and mission statement for the Reserve Force, which was adopted, and urged the DND/CAF to undertake a comprehensive review of the Reserve Force.[v] A comprehensive review is also planned by the DND/CAF to optimize the Reserve Force’s structure for tasks and operations.[vi] The Rationalisation of the Primary Reserve Steering Committee was established, although its focus is on determining the number of sustainable full-time positions and not on a comprehensive review.[vii]

In the past decade, successive Chiefs of the Defence Staff have provided written guidance to the CAF on their vision and intent for the Reserve Force; their views varied widely. In 2007, General Hillier stated that Reserve and Regular Forces were to be more closely integrated and that he expected Reservists to sign up for operations, which required them to be fit (including medically), employable and deployable.[viii] Four years later, General Natynczyk was much less prescriptive in his guidance, directing that the Reserve Force be largely a part-time entity that is to be operationally prepared with reasonable notice.[ix] The definition of “reasonable” was not expressed. One year later General Lawson’s guidance was more closely aligned with his predecessor’s, stating that the Reserve Force is largely part-time and shall be maintained at directed levels of readiness. Again, the term “directed levels” was not further described.[x]

Regardless, for the last quarter of a century Reservists have participated in expeditionary operations in the Balkans, the Middle East and Africa, and humanitarian crises such as in Haiti and the Philippines, largely as augmentees to the Regular Force. In fact, 13,038 members of the Reserve Force have deployed in 27 UN, NATO and federally mandated overseas operations since 1994.[xi] Although it is almost impossible to predict the future needs of the Armed Forces, contemporary global conflicts indicate that Reservists will continue to be integrated into future expeditionary missions.

Also, Reserve Forces are increasingly tasked during domestic operations such as providing security at international events and responding to natural disasters. Reservists are ideal for missions within Canada as they are located in communities throughout the country. 8,087 Reservists have participated in domestic operations since 1997 (11,000 were also on stand-by in case the year 2000 problem, or Y2K, manifested).[xii]

Ultimately, the consequence of the integration of Reservists in CAF operations and missions over the past 25 years is that the Primary Reserve evolved from a strategic supply of personnel into a viable operational asset.

The Need for a Medically Fit Reserve Force

The Army’s divisional force generation formula uses a 5:1 ratio for expeditionary operations and a 3:1 for domestic operations. Therefore, in order to force generate ten Territorial Battalion Groups of 250 people each, the Army requires a pool of 7,500 fit, employable and deployable Reserve Force personnel.[xiii] The Naval Reserve’s Maritime Coastal Defence Vessels are largely manned by Reservists and lately other vessels have begun to employ Reservists on short notice taskings.[xiv] The Royal Canadian Air Force has an employment model whereby Regular and Reserve components are completely integrated as per Total Force. As such Air Reserve personnel must be medically fit as they often switch between Class “A” and Class “B” contracts, to meet surge requirements.[xv]

CAF commanders are ultimately responsible for the health and wellbeing of their subordinates.[xvi] They must attest yearly to the readiness of their personnel in an Annual Personnel Readiness Verification Report, including being medically prepared.[xvii]

Primary Reservists must be medically fit in order to meet the employment and deployment standards of Universality of Service.[xviii] The PHA is also a tool to establish a person’s baseline medical fitness and it builds a historical health profile. By not having members regularly medically assessed, it could cause compensation and benefit issues if a Reservist sustains an illness or injury attributable to service and applies for Reserve Force Compensation or seeks benefits from the Service Income Security Insurance Plan or Veterans Affairs Canada post-release, as there may be insufficient proof to make a claim. Conversely, a member could seek compensation and benefits by blaming a pre-existing condition or an injury sustained in civilian life on the CAF. As such, the PHA would be protecting both the member and the organization.[xix]

The Issue

There is a divergence between the administrative need to have a medically fit Primary Reserve, and the requirement to adhere to medical regulation. Annex B details the regulations, orders and directives relevant to the medical fitness of the Reserve Force.

The Canadian Forces Military Personnel Management Doctrine states “Military personnel policy does not exist in a vacuum. All personnel policies must be integrated and coordinated to ensure alignment with legislation, regulations, strategic goals and other personnel policies…Military personnel policy must be integrated, synchronized and coordinated across the CF as a whole and adapted as necessary to support the components and sub-components of the Total Force.”[xx] However, the legal, regulatory and policy frameworks surrounding the medical fitness of Primary Reservists are not harmonized as articulated in the tenets of the Military Personnel Management Doctrine.

In its current iteration, Queen’s Regulations and Orders 34.07-Entitlement to Care is vague in almost all areas of Reserve personnel’s entitlement to medical services. As noted by Colonel M.L. Quinn, former Director of Health Services Reserve, this ambiguity leads to different interpretations and applications and a considerable amount of healthcare providers’ time is devoted to determining entitlements.[xxi]

To illustrate, the DND/CF Ombudsman’s 2008 Report Reserved Care: An Investigation into the Treatment of Injured Reservists, established that it was generally accepted that Reserve personnel who serve on a Class “B” contract of less than 180 days were only entitled to the same access to CAF medical services as members on Class “A” service. However, investigators found no legal basis for the distinction in Class “B” service based on the length of the contract. Canadian Forces Health Services Group personnel interviewed for the investigation were unable to provide a legal or regulatory basis for the different levels of care. Moreover, several health care providers cited Chapter 34.07 of the Queen’s Regulations and Orders as the reference, but it is not clearly stated in the regulation.[xxii]

The Queen’s Regulations and Orders Chapter 34-Medical Services was last updated in 1985.[xxiii] Since then, Reserve Force Personnel have actively trained for and participated in domestic and expeditionary operations. Moreover, the three CAF Elements now depend upon the Primary Reserves to force generate for arctic and coastal defence, and Reservists are completely integrated into Air Force organizations. As such, commanders require their Reserve Force personnel to be fit for employment and deployment. The Defence Administrative Order and Directive 5023-1 Minimum Operational Standards Related to Universality of Service mandates that all Primary Reservists must be free of medical conditions that would limit their ability to be employed and deployed. CAF Military Personnel Instruction 20/04 is more prescriptive, requiring Primary Reservists to meet the minimum medical standards for their military occupation and have a current medical on file. Further still, commanding officers are responsible for the health and wellbeing of Reservists under their charge, and must attest yearly that their personnel are medically fit. Nonetheless, as the Queen’s Regulations and Orders Chapter 34.07 is written, Reserve Force personnel on Class “A” and Class “B” service under 180 days are only authorized to receive a PHA if the requirement is directly attributable to the performance of a specific military duty. As noted by the Canadian Forces Health Services Group legal counsel, “(p)ut simply, the mere fact that a Reservist may deploy at some point in the future is insufficient to justify performing a PHA at public expense.

”[xxiv]

The lack of provision of PHAs to Reservists is problematic. In writing the Master Implementation Directive for Territorial Battalion Groups, the Army could not direct members assigned to these groups with expired PHAs to be medically assessed, as there was no policy to support the order.[xxv] Due to this constraint, the Master Implementation Directive states that the Immediate Response Units, comprised of Regular Force Personnel, remains the Army’s first line of response for short-notice domestic operations.[xxvi] Yet, as demonstrated during the Calgary floods of 2014, Primary Reservists continue to be the first boots on the ground.[xxvii] The Naval Reserve leadership has noted that the pool of ready personnel is continuously shrinking, partly due to members not having a valid PHA.[xxviii] Moreover, many Reserve aviation technicians are responsible for servicing and maintaining planes and helicopters and as one observer stated “we cannot have a person working on an aircraft who is not healthy

”.[xxix]

Currently, Reserve commanding officers must caveat in their Annual Personnel Readiness Verification report that they cannot attest to the medical fitness of their members.[xxx] Moreover, unlike the Regular Force whose members receive their primary care from CAF medical services, Reserve commanding officers may lack information on their subordinates’ health, who may not have a primary care provider. As such, some have concerns about their liability when members are training and their medical fitness is unknown.[xxxi]

There are consequences of the policy issues for Reserve personnel as well. At present, some Reservists are being passed over for employment opportunities because their PHA is expired and as such they do not meet the requirements of the CAF Military Personnel Instruction 20/04 and are in breach of Universality of Service.[xxxii]

Work on amending Queen’s Regulations and Orders Chapter 34 has been ongoing since at least 2003, when the Reserve Access and Entitlement to Health Care Working Group was established with the mandate to review the regulation and to discuss the specific issue of Primary Reservists’ entitlements.[xxxiii] As of June 2015, the amendment is still in draft status. However, if approved, its current iteration provides a broader scope of entitlement to health care and services for Primary Reservists, specifically indicating a right to assessments of medical fitness as required.[xxxiv]

Meanwhile, interim guidance has been issued and initiatives have been undertaken in order to address the gaps identified by the DND/CF Ombudsman in 2008’s Reserved Care. On 16 July 2009 the Canadian Forces Health Services Group issued an interim guidance on the delivery of healthcare to Reservists while the Queen’s Regulations and Orders Chapter 34 is being amended. This document directs that all Primary Reservists, regardless of class of service, who present at CAF medical facility, should be evaluated. It also clearly indicates that members on a Class “B” employment contract over 180 days receive the same level of care as Regular Force personnel, as do Reservists who are continuously employed on short full-time contracts that add up to 180 days. However the guidance also indicates that it is not intended to address the PHA policy.[xxxv] The Vice Chief of the Defence Staff reiterated this commitment in a 2011 memorandum, as the 2009 interim guidance was not being applied consistently across the CAF.[xxxvi]

Efforts have also been made to address the medical fitness of Reservists. In 2009, 4 Health Services Group Detachment Toronto undertook to medically screen all Primary Reservists with an expired PHA within its area of responsibility in order to meet the demands of domestic operations, including the upcoming Olympics and world summits that were being held in Canada in 2010.[xxxvii] A proof of concept trial was undertaken in British Columbia in late 2010. In 2011, the Surgeon General expanded the initiative, stating in a memorandum that “(t)he provision of PHAs and immunizations to all Primary Reserve members, regardless of class of service, ultimately must be rolled out across the country, be sustainable and become a baselined activity…

”.[xxxviii] As a result, another proof of concept trial was conducted in five regions to meet the needs of the Army’s Arctic Response Company Groups in 2012.[xxxix]

In November 2014, a draft interim guidance was presented to participants of the Clinic Leaders Professional Training Conference in Ottawa detailing the reasons for which a PHA will be booked at a CAF clinic (e.g. promotion, full-time employment, post-deployment). It also states that “(f)or all other Class A PHAs, it will be dependent on the availability of Health Care Providers at the CF Clinic. Supporting clinics and Reserve Field (Ambulances) will continue to provide PHAs as money and resources permit

”.[xl] Although the Surgeon General stated in 2011 that PHAs for all Primary Reservists must be provided across the country and baseline funded, the current practice is to continue to provide PHAs to the Reserve cohort if resources and funds are available.

Section III - Demand

Demographic Considerations

General Demography

Age

Of 26,777 members captured in the Human Resource Management System (HRMS) data extract used for this study, 28% of Primary Reservists are over the age of 40.[xli] Over three-quarters of the Army and Naval Reserve’s personnel are under the age of 40. However, the Air Reserve’s age demographic is the opposite, with only 16% of its members under the age of 40. Unlike the Army and Naval Reserves who recruit largely from the student population, the Air Reserve’s members are mainly ex-Regular Force personnel. Also, due to the largely technical nature of the work performed, the Air Reserve recruits skilled applicants. These two factors are the cause for an older workforce.[xlii]

Primary Reservists by Age Group and Organization

| Age | CA | RCN | RCAF | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 40 | 15,103 | 2,493 | 314 | 1,419 | 19,329 |

| Over 40 | 4,009 | 783 | 1,617 | 1,039 | 7,448 |

|

Grand Total |

19,112 | 3,276 | 1,931 | 2,458 |

26,777 |

See Annex C Appendix 1 for a graph depicting the age of Primary Reservists.

Gender

According to the HRMS data extract, 4,456 Primary Reservists, or 17%, are female. The Army has a largely male population, at 88%.

Primary Reservists' Gender by Organization

| Gender | CA | RCN | RCAF | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 2,261 | 987 | 438 | 770 | 4,456 |

| Male | 16,851 | 2,289 | 1,493 | 1,688 | 22,321 |

| Grand Total | 19,112 | 3,276 | 1,931 | 2,458 | 26,777 |

Military Data

Organization of Employment

The Canadian Army

71% of Primary Reservists are enrolled with the Canadian Army. Army Reservists are employed in over 135 communities across Canada.

As Army Reserve units are geographically dispersed and are usually integrated in their communities, they are ideally suited for domestic tasks. The Army maintains Immediate Response Units and Territorial Battalion Groups as the principal model for its domestic capability; Reserve Brigades are the primary force generators for the Territorial Battalion Groups.[xliii] Each of the ten Brigades is responsible for one Territorial Battalion Group, comprised of about 250 personnel. Members of these groups must present themselves at the mounting area within 72 hours of receiving an order.[xliv]

The Reserves are also the primary force generators for the Canadian Army’s Arctic Response Company Groups. Four Arctic Response Company Groups are maintained (one per Area), and Brigades rotate responsibility. As Arctic Response Company Groups are not the designated first responders in an emergency, members tasked to these groups must be ready to deploy within 30 days’ notice.[xlv]

The Royal Canadian Navy

The Royal Canadian Navy commands 12% of the Reserve Force. Naval Reservists are largely employed in one of 24 Naval Reserve Divisions located across the country.[xlvi] Whereas the Canadian Army mostly trains its personnel in order to contribute teams of soldiers for operational requirements, the Naval Reserve also conducts collective training but largely force generates sailors on an individual level.[xlvii]

Also, the Royal Canadian Navy sources personnel to operate its 12 Maritime Coastal Defence Vessels primarily from the Naval Reserve. The Maritime Coastal Defence Vessels’ primary mission is coastal surveillance and patrol including general naval operations and exercises, search and rescue, law enforcement, resource protection and fisheries patrols.[xlviii]

The Royal Canadian Air Force

The Royal Canadian Air Force employs 7% of Reserve Force members. Having implemented the Total Force concept, Regular and Reserve Force personnel are completely integrated into Air Force wings, squadrons and units. Also, within the Royal Canadian Air Force, three flying squadrons and four construction engineering units are largely staffed with Reservists. [xlix]

The Air Reserves has a high percentage of technical trades. Reserve Force technicians work 12-15 days per month, doing shift work. They perform the same tasks, in the same unit, as their Regular Force counterparts, but on a part-time basis.[l]

Other DND/CAF Organizations

9% of Reserve Force personnel are employed by other DND/CAF organizations, the largest of which is the Health Services Reserve, with approximately 1,400 members. The organization force generates trained personnel to support, augment and sustain the Canadian Forces Health Services Group's domestic and expeditionary commitments and to provide health services support to other Reserve elements.[li]

Other organizations that have a Reserve Force component include the Judge Advocate General’s Office, the Military Police Group and the Special Operations Forces.

See Annex C Appendix 1 for a graph depicting organization of employment.

Location of Work

The provinces where the largest percentages of Reservists work are Ontario (36%), Quebec (24%), British Columbia (10%) and Nova Scotia (8%). The provinces and territories where the smallest percentages of Reservists work are the Yukon (0%), Nunavut (0%), the Northwest Territories (0.2%) and Prince Edward Island (0.8%).

Count of Primary Reservists by Location of Work and Organization of Employment

| Province | CA | RCN | RCAF | Other | Grand Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

AB |

1,361 | 171 | 99 | 258 | 1,889 |

| BC | 1,820 | 488 | 201 | 200 | 2,709 |

| MB | 561 | 128 | 226 | 100 | 1,015 |

| NB | 826 | 88 | 53 | 21 | 988 |

| NL | 563 | 83 | 112 | 20 | 778 |

| NS | 1,304 | 337 | 379 | 268 | 2,288 |

| NT | 57 | 0 | 9 | 14 | 80 |

| ON | 6,973 | 1,045 | 498 | 1,094 | 9,610 |

| PE | 143 | 77 | 0 | 2 | 222 |

| QC | 4,898 | 752 | 331 | 419 | 6,400 |

| SK | 606 | 107 | 23 | 62 | 798 |

| Grand Total | 19,112 | 3,276 | 1,931 | 2,458 | 26,777 |

| As a % of Primary Reserves | 71%* | 12%* | 7%* | 9%* | 100% |

*Percentages are rounded.

See Annex C Appendix 2 for a geographic representation of this data.

Years of Service

38% of the Reserve cohort has served less than five years (although, some members may have previously served in the Regular Force). Slightly more members (42%) have been in the CAF for five to fifteen years. 12% of Reservists have served between 15 and 24 years and 7% have been Primary Reservists for more than 25 years.

Counts of Primary Reservists’ Years of Service by Organization*

| Organization | 0-4 | 5-14 | 15-24 | 25+ | Grand Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA | 7,941 | 7,690 | 2,186 | 1,247 | 19,064 |

| RCN | 1,080 | 1,469 | 433 | 291 | 3,273 |

| RCAF | 568 | 944 | 321 | 89 | 1,922 |

| Other | 687 | 1,154 | 406 | 204 | 2,451 |

| Grand Total | 10,276 | 11,257 | 3,346 | 1,831 | 26,710 |

* Ecludes 67 records where the member's Enrolment date was null.

See Annex C Appendix 1 for a graph depicting years of service.

Retention and Attrition

The Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis administered the CAF Primary Reserve Retention Survey for the first time in 2012. 1,786 Primary Reservists completed the questionnaire. Overall, 40.7% of Primary Reservists intended to leave the CAF within five years. Most often, the reason for leaving was to enter the civilian workforce, where they could receive a higher salary.[lii]

The Primary Reserves largely recruits young adults who are either finishing high school or undertaking post-secondary education; the education reimbursement benefit offered to Primary Reserves is a contributing factor to recruiting students. In the Naval Reserve, a Reservist serves for approximately three years.[liii]

Furthermore, a study conducted by Director Research Personnel Generation in 2013 revealed that 56% of Naval Reservists who joined the CAF between 2002 and 2007 had released by their fifth year of service, compared to 35% of all CAF personnel (this figure includes Regular Force members).[liv]

This information is relevant to tabulating the cost of providing PHAs to all Primary Reservists as 38% of members have served less than five years, and accordingly many will be released prior to the validity of their enrolment medical expiring.

Retention After x Years of Service*

| Year of Service | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naval Reserve | 84% | 70% | 59% | 51% | 44% |

| All CAF | 87% | 79% | 73% | 69% | 65% |

*Data compiled by Director Research Personnel Generation 5-4 2013

Time in Rank

71% of Primary Reservists have been at their current rank for less than five years. Over a quarter of members have not been promoted in over 5 years, with 3% having stayed at their current rank for over fifteen years.

This information is pertinent to this study as Reservists are medically assessed prior to being promoted and for many, it is the only type of medical they receive throughout their career, unless they undertake full-time employment or are operationally deployed.[lv]

Percentage of Primary Reservists' Time in Rank by Organization*

| Time in rank | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organization | 0-4 | 5-14 | 15-24 | 25+ | Grand Total |

| CA | 74% | 22% | 3% | >1% | 100% |

| RCAF | 72% | 24% | 3% | >1% | 100% |

| RCN | 55% | 40% | 4% | >1% | 100% |

| Other | 61% | 35% | 3% | >1% | 100% |

| All Primary Reserves | 71% | 25% | 3% | >1% | 100% |

*These figures were derived from a DGMPRA HRMS extract current as of 4 December 2014

Medical Information

Distance to CAF Medical Installations

Part of the dilemma in providing PHAs to Reservists is that, unlike Regular Force personnel who work on military bases and wings where CAF health services centres are located, Reserve Force members work in communities across Canada often without a CAF medical installation in close proximity.

In examining the HRMS data extract, there are 57 Reservist work locations that are over 100 kilometres away from a CAF medical clinic. 76 work locations are over 100 kilometres away from a Reserve Field Ambulance and 47 locations are over 100 kilometres away from both. 3,508 Reservists live over 100 kilometres away from CAF Medical installations. Of note, 19% of this group, or 676 members, have an expired medical, 210 of them over the age of 40.

Percentage of Primary Reservists' Proximity to Base Clinic or Reserve Field Ambulance by Province and Organization

| CA | RCAF | RCN | Other | Grand Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB | <100km | 88% | 100% | 100% | 99% | 91% |

| 100km + | 12% | 1% | 9% | |||

| BC | <100km | 73% | 100% | 100% | 96% | 82% |

| 100km + | 27% | 4% | 18% | |||

| MB | <100km | 100% | 100% | 100% | 99% | 100% |

| 100km + | 1% | 0% | ||||

| NB | <100km | 62% | 100% | 100% | 67% | 68% |

| 100km + | 38% | 33% | 32% | |||

| NL | <100km | 86% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 90% |

| 100km + | 14% | 10% | ||||

| NS | <100km | 90% | 82% | 100% | 100% | 91% |

| 100km + | 10% | 18% | 0% | 9% | ||

| NT | <100km | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |

| ON | <100km | 92% | 100% | 87% | 99% | 93% |

| 100km + | 8% | 0% | 13% | 1% | 7% | |

| PE | 100km + | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |

| QC | <100km | 80% | 100% | 74% | 74% | 80% |

| 100km + | 20% | 26% | 26% | 20% | ||

| SK | <100km | 93% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 4% |

| 100km + | 7% | 6% | ||||

| Grand Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | |

See Annex C Appendix 3 for a geographic representation of this data.

Reservists with Expired PHAs

Of the 26,777 Reservists listed in the HRMS data extract, 6,883, or 26%, have expired PHAs.[lvi] Of those, 3,470 are under the age of 40, and 3,413 are over the age of 40. The Army is the organization with the highest amount of expired PHAs (5,081), followed by the Air Force (551), the Navy (529), and Others (722). Of the Other organizations, 245 members are employed in health services.

The number of expired PHAs in the Reserve cohort could potentially increase in the next couple of years. Reserve personnel who were employed during the Olympics in 2010 and who deployed to Afghanistan (where the combat mission ended in 2011) were medically assessed prior to their engagements; if they are under the age of 40 their PHAs will expire in 2015 and 2016. Moreover, the reduction of multi-year permanent Class “B” positions from about 7,500 to 4,500 could contribute to the increase in expired PHAs as Reservists working on these types of contracts are medically assessed prior to employment.

Count of Primary Reservists' with Expired PHAs by Age and Organization

| Age as of 31 Dec 14 | CA | RCAF | RCN | Other | Grand Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 40 | 2,931 | 36 | 259 | 245 | 3,470 |

| 40+ | 2,150 | 516 | 270 | 477 | 3,413 |

| Grand Total | 5,081 | 551 | 529 | 722 | 6,883 |

See Annex C Appendix 3 for a geographic representation of this data.

Reserve Force Personnel Who Have a Primary Care Physician

Reservists generally receive health care services from the province in which they reside. An informal poll conducted as part of this study showed that nationally, 3,952 Reservists, or 38% of respondents, do not have a family doctor in which they can seek routine care or consult for specific issues. The Toronto area was the region with the highest percentage of Reservists with a family doctor (85%). 62% of polled Reservists are without a family physician in Western Quebec, including the Montreal region.

According to Statistics Canada, in 2013 15.5% of Canadians 12 and over reported that they did not have a regular medical doctor. This percentage increased to almost 35% for males aged 20-34, which is demographically comparable to the age and gender of the Reserve cohort.[lvii]

It is important for Primary Reservists to have access to a primary care provider, due to the physically challenging nature of the tasks and training military personnel undertake. If Primary Reservists do not have access to a general practitioner for routine health care or to consult for specific issues, they may have undiagnosed conditions or issues that they are not seeking help for and are participating in training and work that may cause them or their co-workers harm and may impact CAF liability and readiness. Also, if members are given PHAs and a condition is revealed, a member should follow-up with their primary care physician. However, if the member does not have a family doctor, the CAF may be liable to take on the member’s care, thus increasing the resource burden.[lviii]

See Annex C Appendix 4 for a geographic representation of this data.

Estimated Annual Demand

As per the calculations below, it is projected that between 4,881 and 6,106 medical assessments would be conducted in a given year in order for Primary Reservists on Class “A” service to be provided with PHAs at the same standard as the Regular Force.

Personnel employed in some air and naval occupations are required to be medically assessed more frequently and by different tests therefore they were removed from the counts.[lix] and [lx] Moreover, as Reservists occupying permanent Class “B” positions are medically assessed prior to employment, the number of positions was removed from the estimate.[lxi]

Low Estimate (Actual Paid Strength)

| Actual paid Strength of Primary Reserves as per 2013-14 Departmental Performance Report | 22,467 |

| Less permanent Class "B" positions | 4,500 |

| Less permanent Class "B" positions | 780 |

| Total | 17,187 |

| # of Reservists under 40 (17,187 x 72%, equivalent percentage to HRMS data extract) | 12,375 |

| # of Reservists over 40 (17,187 x 28%, equivalent percentage to HRMS data extract) | 4,812 |

| Annual # of PHAs for under 40 cohort as per 5 year period of validity (12,375/5) | 2,475 |

| Annual # of PHAs for over 40 cohort as per 2 year period of validity (4,812/2) | 2,406 |

| Total annual demand, low estimate | 4,881 |

High Estimate (Total Strength)

| Total Strength of Primary Reserves as per HRMS data extract | 26,777 |

| Less permanent Class "B" positions | 4,500 |

| Less aircrew and diver occupations | 780 |

| # of Reservists under 40 (21,497 x 72%, equivalent percentage to HRMS data extract) | 15,477 |

| # of Reservists over 40 (21,497 x 28%, equivalent percentage to HRMS data extract) | 6,020 |

| Annual # of PHAs for under 40 cohort as per 5 year period of validity (15,477/5) | 3,010 |

| Annual # of PHAs for over 40 cohort as per 5 year period of validity (15,477/5) | 3,096 |

| Total annual demand, high estimate | 6,106 |

Section IV - CAF Health Services’ Capacity to Provide PHAs to All Reservists

CAF Health Services Centres

There are over thirty CAF health services centres (clinics and detachments) located throughout Canada.[lxii] The current Canadian Forces Health Services Group’s Primary Health Care Model was created as part of the RX2000 renewal program launched in 2000. Developed through a series of working groups and advisory committees, it established the optimal size of clinics and the number of medical personnel required to provide in-garrison health services to Regular Force members and entitled Reservists.[lxiii] Five types of clinics were established, from a detachment with less than 500 clients with few clinicians and health services limited to preventative health care to a clinic with more than 5,000 clients, providing preventative medicine and specialist care, laboratory and diagnostic imaging, physiotherapy and pharmaceutical services (see Annex D).[lxiv]

Within a health services centre, primary care is delivered through Care Delivery Units, comprised of civilian and military healthcare professionals. All Regular and Reserve Force units are assigned to a specific Care Delivery Unit, although Primary Reservists may only access services if entitled.[lxv] CAF members receive the same care as they would in a civilian family practice, such as walk-in services (colloquially known as sick parade), booked appointments, and medical assessments including PHAs.[lxvi]

Last year the Canadian Forces Health Services Group published the Surgeon General’s Report 2014. The document describes the breakdown of a typical day of patient encounters at a clinic as 57% scheduled appointments, 35% sick parade consultations and 8% periodic health assessments.[lvxii] At first glance, it would appear that not much clinic time is spent conducting PHAs. However, the percentages do not reflect the amount of a clinic’s time spent on an activity, but rather the number of types of appointments. Compared to PHAs, scheduled appointments and sick parade consultations are relatively short in duration.[lxviii] Therefore it makes sense that the percentage of PHAs conducted in a day reported in the Surgeon General’s Report 2014 is low.

As part of this study a survey was conducted to determine current resource requirements to provide PHAs in the health services centres, in order to project increase in volume should PHAs be provided to all Primary Reservists. Survey respondents (usually the base/wing surgeon or clinic manager), were asked to provide the time allocated in the clinic’s schedule to conduct Parts I and II of the PHA. Results indicated that most clinics allot 30-45 minutes for Part I of the PHA and 45 minutes to one hour for Part II.

Survey respondents were also asked to provide the clinic’s average total monthly hours per type of clinician, and the amount of the total hours these clinicians dedicate to conducting PHAs; this information enabled the determination of the average clinician time spent conducting PHAs. Results were as follows:

- CAF medical officers: 20%;

- Contracted civilian physicians: 26%;

- CAF physician’s assistants: 23%;

- Contracted civilian nurse practitioners: 16%; and

- Medical technicians: 24%.

Considering the geographic distribution of Reservists throughout Canada and the estimated annual demand calculated in Part III of this study (4881 low, 6106 high), the table found at Annex E depicts the annual increase in the number of PHAs that CAF medical clinics and detachments would be required to perform should PHAs be provided to all Reservists. As per survey responses, the average of 1.5 hours was used to calculate the increase in time.

Respondents also provided anecdotal evidence demonstrating the possible resource constraints they may encounter should they be required to take on the additional PHAs.

As per the Primary Health Care Model, not all health services centres provide laboratory services onsite. 16 of the 29 survey respondents outsource at least part of a PHA-related screening test. Some of the clinics that do provide laboratory services noted that the increased demand would overwhelm their capacity.

Some clinics are not currently staffed to accommodate the increased need for PHAs because Class “A” Reservists, who are not normally entitled to care, were not considered in calculating the staffing baseline required to provide services in health services centres as per the Primary Health Care Model. Health services centres in Toronto and London, where not many Regular Force personnel are patients but over 5,000 Reservists work in their area of responsibility, would be overwhelmed by the increased demand.

Some military installations like Borden and Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu house several schools, and others like Meaford and Wainwright are training centres where units conduct exercises. As such, their population is largely transient with personnel numbers varying depending on courses and training being run. Therefore, the health services centres at these locations may be able to accommodate an increase in the provision of PHAs at one time, yet be overwhelmed at another, as their population fluctuates.

In reviewing the websites of 16 health services centres, on average, 1.5 hours of a clinic’s day is devoted to sick parade. This leaves about six hours in the schedule for clinicians to conduct appointments related to acute care and chronic disease management, medical assessments including PHAs, case conferences, and patient administration such as reviewing test results, updating records and preparing correspondence.[lxix] Only three health services centres that responded to the survey could handle a last minute request for a PHA either because they have a low population or because they have time built into their schedule. Other clinics would handle the request by cancelling or bumping another appointment, having the clinician conduct the PHA during personal time such as during lunch or a physical training period, or use the time blocked in the scheduler to conduct administrative tasks.

In reviewing the Canadian Forces Health Services Group's position charters for this study, it was noted that in some locations, such as in Edmonton, Petawawa and Gagetown, not all military health personnel are attached to the health services centres.[lxx] Some are posted to field hospitals and/or ambulances (mobile medical units), and only work at the clinic while in garrison. Furthermore, there are positions in some health services centres that are filled on a Class “A” basis by Reservists.

Moreover, the organization charts showed several vacancies at many of the health services centres. On average, 15% of medical officer/contracted civilian physician positions were vacant, as were 29% of physician’s assistant/nurse practitioner positions and 15% medical technician spots. Personnel in some clinics are double-hatted, acting both as base surgeon and a medical officer or clinic warrant officer and medical technician.

As such, some health services centres may be having difficulties meeting current demand without the increase in PHA provision. Gagetown noted in their survey response that due to the clinician shortage at their location, they are booking PHAs 3 months in advance. The Shilo clinic indicated that it employs two medical officers, one physician’s assistant and ten medical technicians and they are having difficulty meeting current demand. Moreover, the base surgeon in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu stated that the detachment in Montreal cannot fulfill the requirement for PHAs in its area so any Reservists who need a PHA are sent to his clinic.

Reserve Field Ambulances

There are 18 Field Ambulances and/or Detachments in the Health Services Reserve Force. As part of this study, a questionnaire was submitted to Reserve Field Ambulances and all 18 responded.

Currently four Reserve Field Ambulances are conducting PHAs. The Field Ambulances in Victoria and Vancouver have been providing PHAs since late 2010, when they conducted the proof of concept trial on behalf of the Director Health Services Reserve. Field Ambulances in Quebec and Winnipeg also indicated that they provide PHAs. The Field Ambulance in Victoria has developed a process for conducting “blitz weekends” which could be adopted and/or adapted by other Reserve Field Ambulances. A study on the provision of medical assessments on Reserve personnel in the United States showed that conducting medical assessments in a group setting such as a blitz weekend is cost effective, as the per person expense was 20 percent lower than if the members were provided the assessment individually.[lxxi]

However, many Reserve Field Ambulances currently are inadequately resourced to conduct PHAs. 10 Field Ambulances presently do not have a portable hearing machine. Moreover, 15 of the 18 Field Ambulances and detachments do not have access to the Canadian Forces Health Information System (the CAF’s electronic health record system) and would require training, which takes about five days to complete.[lxxii] Also, 12 Reserve Field Ambulances do not have physician’s assistants or medical officers in their unit to conduct Part II of the PHA.[lxxiii]

See Annex F for a table detailing the number of blitz weekends that would have to be conducted annually if Reserve Field Ambulances were to take on the responsibility of providing PHAs to all Reservists.

393 million dollars have been allocated to military health care for fiscal year 2015-2016.[lxxiv] However, according to Chief Military Personnel’s business plan for 2015-2016, sustainment of the current level of health care will result in increasing funding pressures.[lxxv] This budgetary constraint could complicate the Canadian Forces Health Services Group's subsidizing an increase in PHA demand.

Nonetheless, providing PHAs to all Primary Reservists could be feasible if other courses of action are considered. Preliminary research conducted as part of this study examined potential options including partnering with other governmental departments whose employees are also assessed for medical fitness, providing a health support allowance similar to the Australian Defence Force, outsourcing to civilian providers, and resourcing Reserve Field Ambulances to conduct the assessments. The Canadian Forces Health Services Group has also reviewed other ways to provide Primary Reservists with assessments of medical fitness separate from this study.

The Canadian Forces Health Services Group will further investigate all courses of action in greater detail to determine the valuation of each of the options, including full costings, and will prepare a report on its findings.

Section V – Areas of Concern

Accreditation

In January 2011, the Canadian Forces Health Services Group received accreditation by the country’s national health services quality authority, Accreditation Canada. In late 2013 it was again accredited “With Commendation”, having surpassed Accreditation Canada’s and the Group’s own standards.[lxxvi]

Benchmarks are established by Accreditation Canada’s Qmentum Program. If the course of action of providing PHAs to all Reservists is not within a health services centre, there are several standards evaluated by the organization that may not be achieved, thus adversely impacting the Group’s rating. For example, if Reserve Field Ambulances provide PHAs, in some locations they will be conducted in armouries as opposed to a clinic, which may not meet Qmentum’s standards for infection control protocols, patient safety, and information management.[lxxvii]

However, the Canadian Forces Health Services Group's subject matter expert on quality and patient safety noted that currently, the accreditation program solely focuses on the health services centres, not Field Ambulances. Moreover, the Canadian Forces Health Services Group is not required to add the Field Ambulances to their accreditation process.[lxxviii]

The Canadian Forces Health Information System

The Canadian Forces Health Information System provides integrated health information services including electronic medical records, dental records, medical and dental digital imagery, laboratory services, and a report-generating system.[lxxix]

There are two concerns regarding the health information system as it pertains to providing PHAs to Reservists. First, any documentation generated by outsourced testing and assessments will need to be forwarded to the Canadian Forces Health Services Group and scanned into the database. One of the benefits of having a pan-CAF electronic record is that it provides a data mining and reporting capability that yields real-time information to support decision-making.[lxxx] However, the system cannot extract information from scanned documents. Therefore, if many Reservists are provided a PHA from a physician outside the DND/CAF, it will be difficult to glean fulsome health information as it pertains to the Reserve cohort from the Canadian Forces Health Information System. As one medical policy advisor noted “it would be a huge standard to lower”.[lxxxi]

The other concern relates to issues that could arise if personnel from Reserve Field Ambulances have access to the Canadian Forces Health Information System. If a user has not logged into the system in a determined time (about three months), their account is frozen.[lxxxii] Reserve units generally stand-down from late May to early September and those with Canadian Forces Health Information System access will be locked out of the system. This could complicate the process for Reserve Field Ambulances to conduct PHAs in the early fall.[lxxxiii]

The Canadian Forces Health Information System contains sensitive information about members’ health. To protect their privacy, a security officer is delegated to monitor usage and enforce policy and security protocols. Security officers should work in the DND/CAF full-time and have extensive knowledge of the system’s training modules, rules and regulations.[lxxxiv] In the case of the Field Ambulance in Victoria, it falls under the purview of the health services centre at CFB Esquimalt for policy enforcement. However, not all Field Ambulances are co-located in the same region as a health service centre therefore there may be an issue with monitoring usage in those locations. In fact, Canadian Forces Health Information System access is currently only authorized in clinic locations due to security concerns.[lxxxv] Therefore, Reserve Field Ambulances conducting PHAs in their location or at Reserve unit armouries are relegated to using paper copies, which is not a preferred method of capturing information.

Reservists’ Ownership of their Personal Health

The CAF prides itself on the notion that it takes care of its personnel. In fact, in 2012 it named its comprehensive framework of programs and services for CAF ill and injured members Caring for Our Own.[lxxxvi] Moreover, the Chief of the Defence Staff states in his Guidance to Commanding Officers that they are ultimately responsible for the health of their subordinates.[lxxxvii]

Nonetheless, as being fit is a condition of service, all military members should ensure that they are healthy, regardless of whether or not they have been ordered to do so. Evidence indicates that some members of the Regular Force are not proactive in ensuring their medical readiness. In fiscal year 2008-2009 the Canadian Forces Health Services Group conducted the Health and Lifestyle Information Survey. Of the 3,884 Regular Force participants, 14% had expired PHAs.[lxxxviii] Moreover, the health services centre in Trenton regularly monitors its personnel with temporary medical categories; in 2014, between 34 and 50 percent of personnel with temporary medical categories were overdue to be reexamined.[lxxxix] However, the third next available appointment (the measurement used to gauge true appointment availability) during most months at the service centre’s Care Delivery Units remained below the 15 day standard.[xc] Therefore, it can be surmised that the expired temporary categories are not due to appointment wait times.

Reservists are generally required to seek care in the province in which they reside but it should not preclude them from addressing health concerns. In fact, they are obligated as per the Queen’s Regulations and Orders Chapter 19.18 Concealment of Disease to notify the CAF if they are suffering from an illness, even if it is only suspected.[xci] It will make it much easier for members of the cohort to ensure they are medically fit if the DND/CAF commits resources to providing PHAs to all Reservists, Yet, as demonstrated with the Regular Force, there is no assurance that personnel will avail themselves even if the service is readily accessible.

Related to the notion of Reservists’ ownership of their personal health are immunizations. Reservists should ensure that their immunizations are current. As members of the Regular Force receive their primary health care from the DND/CAF, their immunizations are reviewed and updated if required during their PHA.[xcii] Most Reservists are not entitled to health care, but should receive core immunizations from the DND/CAF if they are not publicly funded in their province and they are operationally required.[xciii] However, in examining the routine schedules of publicly funded immunization programs in Canada, most vaccinations that are mandated by the DND/CAF’s Director Force Health Protection are publicly funded in all provinces and territories.[xciv]

There are two exceptions. First, the influenza vaccine is not publicly funded for healthy adults in British Columbia, Quebec, New Brunswick and Newfoundland. Although the DND/CAF could provide the vaccine to Reservists in those provinces, it is currently only a recommended vaccine in the DND/CAF, not mandatory as per the Director Force Health Protection guidelines.[xcv] Even still, if the DND/CAF were to offer the influenza vaccine to Reservists residing in the provinces where it is not publicly funded, it would cost about $60,150 a year.[xcvi]

The Canadian Immunization Guide recommends the Hepatitis A vaccine for at-risk individuals only. The immunization is not publicly funded in all provinces and territories for healthy adults who do not travel to at-risk countries.[xcvii] Members of the Regular Force are vaccinated against Hepatitis A as they deploy to countries where the disease is prevalent. Reservists will also be vaccinated if they are deployed. The issue with the Hepatitis A vaccine is that immunity develops within 2 weeks of the first dose and two doses are required.[xcviii] If Reservists were to deploy in response to a sudden international crisis, they would already have to be vaccinated (although most Reservists on international deployments have months to prepare, some occupations such as the medical professions could be required in response to disaster relief). If the DND/CAF were to offer the Hepatitis A vaccine to all Reservists, it would be a one-time cost of $654,700 to $780,300.[xcix]

Medico-legal Liability of the DND/CAF Clinicians

People without a family physician, also known as orphan patients, are a reality of Canadian society. According to the Canadian Medical Protective Association, physicians who treat or assess patients must ensure that the patient is properly discharged. This includes assuring that the patient has a physician that can oversee follow-up care.[c] An informal poll conducted as part of this study showed that 38% of Reservists who responded do not have a family doctor.

There are concerns within the DND/CAF medical community that providing PHAs to Reservists may impact the medico-legal liability of clinicians who assess a Reservist and a health issue is uncovered. As Reservists generally do not receive health care from the DND/CAF, they would have to follow-up on any identified issues with their family physician.[ci] Yet, 38% of the Reserve cohort does not have a family doctor.

The Canadian Forces Health Services Group’s legal advisors contend that if a Reservist requires follow-up care as a result of an issue discovered during a PHA, the DND/CAF must refer them to a family physician. If the member does not have a doctor, the DND/CAF should assist them in finding a physician, or a clinic, which can provide follow-up care. If a resource cannot be found, then the DND/CAF is responsible for providing care to the member.[cii]

Therefore, the medico-legal responsibility of the DND/CAF in ensuring that Reservists with issues diagnosed during PHAs are cared for could potentially impact the Canadian Forces Health Services Group’s resources, as clinicians either spend time helping Reservists access follow-up care or take on the care themselves. As such, some health services centres that have difficulties meeting current demand may become overwhelmed. Also, it would create difficulties for Reservists who do not live in proximity of a health services centre in that they would have to travel to access care.

Section VI - Conclusion

“Why would the requirement of having a current medical on file, stated in ADM (HR-Mil) Instruction 20/04, NOT apply to Class “A” Reserve Service members? Again, why would this situation, i.e. having members on Class "A" Reserve Service with expired (not current) medicals, be ok?”

Although it could be easily assumed that the excerpt above is quoted from a recent statement, it was actually copied from an email written by a medical officer working in clinical policy in February 2005. The medical readiness of the Primary Reserves, and the broader argument of Reservists’ entitlement to DND/CAF health care, has been a contentious issue for over a decade.

There are three initiatives currently underway in the DND/CAF that make now an opportune time for stakeholders to re-examine the provision of PHAs to all Reservists regardless of class of service.

The first project is the comprehensive review of the Reserve Force as per the recommendation proposed in the Primary Reserve Employment Capacity Study in 2011. Once DND/CAF leadership define the role of the modern Reserve Force, administrative policies and directives should be aligned and updated, including instruments related to operational and medical fitness.

The second initiative is the updating of Queen’s Regulations and Orders Chapter 34-Medical Services. Although the Canadian Forces Health Services Group has been working on the update for over a decade, it is possible that the amendments, if approved, could be made within the year. The updated version provides for assessments of medical fitness for Primary Reservists.

The third undertaking is the PHA Renewal initiative. If process amendments are adopted, the periodicity of the assessment and/or the tests conducted as part of the exam may change.

Another point to consider is the increase in public and media interest in the Reserve Force, especially since the events that occurred in Ottawa in October 2014. Presumably, any serious injury or death of a Reservist sustained during training or a domestic operation will become known in the public domain. It could potentially have repercussions for the DND/CAF if the Reservist was employed without a valid medical assessment, even if it were not attributable to the cause of the catastrophic incident.

As noted by Richard Weitz in The Reserve Policies of Nations: A Comparative Analysis, although it is expensive to provide Reservists with health and other benefits offered to Regular Force personnel, it is becoming more difficult, both morally and politically, to maintain status quo when Reserve and Regular Force roles are increasingly undifferentiated.[ciii] The CAF’s Primary Reserve has evolved from a strategic to a viable operational asset. As such, it should be ensured that the cohort is fit to train and to fight.

Annex A: Methodology

Information for this study was collected using various methods.

Documentation Research

A cull and analysis was undertaken of existing policies and documentation pertaining to medical services, periodic health assessments, occupational medicine, Reserve Forces and its personnel. Information was gleaned from the following sources:

- Previous DND/CF Ombudsman investigations;

- Canadian Forces Health Services Group;

- DND intranet;

- Federal and provincial governments;

- Canadian medical and health related associations;

- NATO and ABCA nations[civ]; and

- Other open sources.

Subject Matter Expert Engagements

Engagements with subject matter experts and other informants were undertaken as required to request information and/or to understand policy and procedure. Meetings were conducted in person or on the telephone, with individuals from the following organizations:

- Director Health Services Reserve;

- Director Medical Policy;

- Director Health Services Delivery;

- Director Force Health Protection;

- Canadian Forces Health Services Group legal, finance and performance measurement personnel;

- Reserve Field Ambulance and CAF medical clinic personnel;

- CAF stakeholders at the Formation and Command levels; and

- Health Canada’s Specialized Health Services Directorate.

Demographic Data

The Total Strength of Primary Reserve personnel was extracted from HRMS Mil (7.5), CAF’s personnel database, on 24 September 2014. The following demographic information was included:

- Service number;

- Sex

- MOSID (occupation code);

- Unit;

- Date of birth;

- Date of enrolment; and

- Date of last medical.

Names were specifically not requested so personnel could not be easily identified.

According to the HRMS data extract, the Total Strength of Primary Reservists is 27,511. Personnel whose date of birth indicated they were over sixty years old and thus beyond the compulsory age of retirement were removed from the spreadsheet. Also, several Primary Reserve units have detachments in different locations; however the address of the detachment is not indicated on the member’s profile in HRMS. Therefore, units with detachments were asked to provide lists of their members’ service number and work location. Lists were matched to the HRMS data and work location was updated when required. Members who were in HRMS but not on lists provided were removed from the HRMS spreadsheet. After making these adjustments, the Total Strength of Primary Reservists used in this report is 26,777.

Other demographic data was obtained from Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis studies, and is referenced accordingly.

Costing Data

Salary costs were derived from the Cost Factors Manual 2014-15 Volume I-Personnel Costs.

Travel expenses were calculated using information from the National Joint Council’s Travel Directive.

Costs for outsourced medical tests and exams were provided by the Federal Health Claims Processing System.

Medical clinic and Field Ambulance organization charts were provided by the Canadian Forces Health Services’ Comptroller Group.

Questionnaires and Surveys

A questionnaire was sent to CAF medical clinics to obtain information relevant to the study (see Appendix 1). It was disseminated via email to clinics and detachments on November 13th 2014. 29 of 33 clinics and detachments responded. A different questionnaire was sent to Reserve Field Ambulances and detachments (see Appendix 2). It was disseminated via email on November 4th 2014. All units responded.

In order to determine the percentage of Reservists who have a family doctor, a request to conduct an informal, voluntary poll was disseminated to all Army, Navy and Air Reserve units through their respective chains of command on November 4th 2014. The information requested included the number of personnel polled, and the number of those polled who have a family physician. 10,472 members participated in the poll.

Constraints

There were three main constraints in conducting this study. First was the integrity of personnel data. Reserve units use various databases and paper files to manage their members, of which one is the CAF personnel database, HRMS Mil (7.5). It was observed that some units might not be updating the database regularly and/or auditing records for accuracy. Some entries were missing dates for enrolment and last medical, and several Reservists who had attained compulsory age of retirement were still active in the database. Some units were asked to submit lists of personnel who work in detachments; in a sampling of 25 of those units, half had over 10% of members not on their nominal roll still active in HRMS. This leads to the conclusion that the number of personnel counted in the Total Strength of the Primary Reserves is probably lower than what is captured in HRMS.

Also, data that was important to capture for this study may not be essential for the Canadian Forces Health Services Group to regularly collect and report on and as such was difficult to retrieve. Separate questionnaires were submitted to CAF medical clinics and Reserve Field Ambulances asking for the information required. Responses were reviewed and analysed with subject matter experts, but a scientific quantitative analysis was not undertaken.

Lastly, there are two regulation and process revisions currently underway. The Queen’s Regulations and Orders on medical services (Chapter 34) is being revised and the proposed amendment, if adopted, will impact Reservists’ access and entitlement to care, including assessments of medical fitness. The proposed Queen’s Regulations and Orders will be sent to the National Defence Regulations Section imminently to review the wording of the instrument; this analysis should last about three months. After that, the updated version will be sent for review and signature to the Chief of the Defence Staff, the Minister of National Defence and the Governor in Council, which should take about 6 months to complete. As there is no direct resource implication, the revised regulation does not require Treasury Board approval.[cv]

Also, the Canadian Forces Health Services Group has established a steering committee that is overseeing the Periodic Health Assessment Renewal initiative. The last time the PHA process was examined was in 2007.[cvi] The existing process was developed before electronic health records were created and evidence-based approaches were used in conducting medical assessments. Moreover, screening tests and other assessments are constantly being updated by the Canadian and American medical associations on preventative care and as such it is necessary to review CAF assessment protocols. The Surgeon General and the Clinical Council endorsed PHA Renewal on September 18th 2014.[cvii] Should any process amendments be adopted, the types of tests conducted during the PHA and the periodicity of the evaluation may change, which in turn could impact the resource burden of providing PHAs to members of the Primary Reserve.

According to subject matter experts, both reviews may conclude in the next 12 to 18 months. The resource requirements tabulated as part of this study are based on the current PHA process.

Annex B: Relevant Regulations, Orders and Directives

Reserve Force Regulations, Orders and Directives

The National Defence Act is the legislative framework under which the DND/CAF is funded and organized, and establishes the Regular and Reserve Force components.[cviii]

The Queen’s Regulations and Orders is the regulatory framework of the CAF, implementing the edicts established in the National Defence Act. Chapter nine of the Queen’s Regulations and Orders is devoted to the Reserve Force. It outlines the Reserve classes of employment: Class “A” service (part-time employment), Class “B” service (full-time employment) and Class “C” service (a member on Class “C” service is employed in a Regular Force position or is on operation approved by the Chief of the Defence Staff).[cix]

The current policy for the administration of the Reserve Force is the Canadian Forces Administrative Order 2-8, - Reserve Force - Organization, Command and Obligation to Serve, which was last amended in 1976. A new Defence Administrative Order and Directive is to be written by the Chief of Reserves and Cadets; it will replace the Canadian Forces Administrative Order 2-8.[cx]

The CAF Military Personnel Instruction 20/04 Administrative Policy of Class "A", Class "B" and Class "C" Reserve Service amplifies Canadian Forces Administrative Order 2-8. The purpose of this instruction is to ensure uniform administration of all Reserve personnel.[cxi]

Medical Regulations, Orders and Directives

The Canada Health Act establishes the requirements for provincial health programs to meet in order to receive transfer payments. In the Act, CAF personnel are excluded from the list of persons entitled to universal health care from the provinces. As such, the Constitution Act, 1867 places responsibility upon the Federal Government for providing medical care to CAF personnel.[cxii]

The Queen’s Regulations and Orders Chapter 34 governs the CAF’s provision of medical services, including personnel’s entitlement to care. According to paragraph 34.07, Reserve Force personnel are entitled to CAF medical services depending upon employment status and/or whether the need is attributable to service.[cxiii]

Spectrum of Care describes the health benefits and services publicly funded and available to CAF personnel. The document reiterates that Reservists are entitled to medical services and benefits only during specified periods of eligibility based on their duty status and the relevancy of their illness or injury to military service.[cxiv]

ADM (HR-Mil) Instruction 11/04 Canadian Forces Medical Standards provides policy direction to health services personnel in assigning medical categories and establishing employment limitations, and provides stakeholders with background knowledge on medical standards and its administration.[cxv] Amplifying this instrument is CFP 154 Medical Standards, an online manual providing a hyperlinked listing of those policies, publications and related documents applicable to CAF Medical Standards.[cxvi]

Canadian Forces Health Services Group Instruction 4000-01 Periodic Health Assessments outlines the procedure for conducting assessments of medical fitness. The PHA process is based on the recommendations of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force but also considers the CAF’s requirement to ensure its personnel are medically fit. The instruction also establishes the frequency in which PHAs will be conducted: except when dictated by occupational requirements or other circumstances, PHAs are provided to CAF personnel under 40 years of age at 5 year intervals, and every two years for members over 40, normally within one month of the member’s birthday. It also provides functional guidance to clinicians in completing medical assessments and determining employment capability.[cxvii]

PHAs are conducted in two parts. During Part I the member completes a medical questionnaire and a medical technician records vital signs (height, weight, waist circumference and blood pressure). The medical technician also conducts a series of screening tests such as visual acuity assessments and audiograms. An electrocardiogram is performed on members at 35 years of age and a lipid screen (via blood draw) is conducted at ages 35, 40 and then every four years thereafter.[cxviii]

Military medical officers and physician’s assistants, and contracted civilian physicians and nurse practitioners are authorized to conduct Part II of the exam. During Part II the questionnaire, test results, and pertinent information will be reviewed with the member. The clinician may also conduct a physical examination and assess the fitness of the member to perform military duties. The base surgeon (or a delegated senior medical officer) reviews the PHA and provides final endorsement.[cxix]

Administrative Regulations, Orders and Directives

There are several administrative policy instruments that are pertinent to the medical fitness of military personnel. Defence Administrative Order and Directive 5023-0 Universality of Service states that the principle of Universality of Service, also known as “soldier first”, commands CAF personnel to be physically fit, employable and deployable for general operational duties regardless of their occupation.[cxx] Furthermore, Defence Administrative Order and Directive 5023-01 Minimum Operational Standards Related to Universality of Service defines being employable and deployable as members having no medical employment limitations that would prevent them from completing tasks and that they are able to perform under physical and mental stress, with little or no medical support and without critical medication. The order specifically states that members of the Primary Reserve must meet the minimum operational standards related to Universality of Service.[cxxi]